Pilot Scale Demystified: How Lab Scale, Pilot Scale, and Full Scale Really Differ

Last Updated on

December 11, 2025

By

Excedr

In biotech and chemical engineering, scale-up isn’t just about doing the same thing at a larger size. Moving from a 2-liter bench-scale experiment to a 200-liter pilot-scale run—or all the way to full-scale production—introduces new variables, risks, and infrastructure demands. Scale affects everything: your flow rates, raw material inputs, process parameters, equipment selection, and how tightly you need to control variability.

And let’s be real: many startup labs blur the lines between stages. Some try to leap directly from early R&D into commercial production, skipping the essential work of validating processes under real-world conditions. But jumping ahead too fast can stall progress. We've seen it happen—overbuilt systems, missed milestones, and costly rework.

As a company that helps labs finance equipment at every stage—from lab benches to pilot plants to full-scale facilities—we’ve worked closely with teams making these transitions. And one thing is clear: defining the scale you’re working at makes your production process far easier to plan, fund, and execute.

This guide breaks down what laboratory scale, pilot scale, and full scale actually mean—not just in terms of volume, but in how processes evolve, what equipment is required, and how operations need to shift.

What Is Lab Scale? (Discovery and Early R&D)

Lab scale—also called laboratory scale or bench scale—is where ideas get tested and early feasibility is proven. At this stage, scientists focus on methodology development, formulation screening, and small-scale experiments to shape hypotheses and refine protocols.

You're working in milliliters to a few liters, often with flexible, low-throughput workflows. The priority is exploration, not efficiency.

Key characteristics of lab scale:

- Small volumes (typically under 10 liters)

- Benchtop equipment and manual workflows

- High variability and fast iteration

- Minimal regulatory constraints

- Focus on process development and optimization

At this scale, you’re not trying to lock in your operating parameters—you’re troubleshooting them. You might explore a chemical reaction’s heat transfer properties or run side-by-side tests with different raw materials. A failed experiment is cheap and instructive.

But don’t mistake early success for scalability. Mass transfer rates may behave unpredictably as volumes increase. Mixing, temperature control, and evaporation can all shift in larger vessels. The transition to pilot scale is where those issues start to surface.

Takeaway: Lab scale proves your science. It doesn’t prove your process.

What Is Pilot Scale? (Bridge Between R&D and Production)

Pilot scale is where your process meets complexity. It’s the bridge between concept and commercial viability—a place to test and validate under more realistic operating conditions.

Batch sizes at this stage range from about 10 to 1000 liters, depending on your application. You're producing enough material to evaluate downstream processing, perform pilot studies, or generate data for regulatory submissions and investors.

What sets pilot scale apart:

- Intermediate volumes (10–1000L, but often field-dependent)

- Modular or semi-automated systems

- Focus on reproducibility and process optimization

- Increasing regulatory and quality control requirements

- Stress-testing of process design and scale-up feasibility

At this point, equipment decisions become more consequential. You may need jacketed reactors with precise temperature and flow rate control, scalable purification systems, and environmental monitoring infrastructure. Pilot plants often simulate production environments with just enough flexibility to adjust.

Pilot-scale work is where you evaluate process scalability—can this chemical process deliver consistent yields when scaled 10x? Can your operating conditions remain stable across longer runs? It’s also where you identify bottlenecks in filtration, material transfer, or reactor throughput.

Why pilot scale matters:

- Surfaces issues not visible at small scale

- Generates process data for validation and tech transfer

- Supports realistic cost modeling and resource planning

- Reduces risk before investing in full-scale or industrial scale systems

Takeaway: Pilot scale is where you pressure-test both science and systems—before mistakes get expensive.

What Is Full Scale? (Clinical or Commercial Production)

Full scale—whether for clinical supply or full commercial production—is where your process must deliver reliably, at volume, and under strict regulatory oversight.

This phase typically involves hundreds to thousands of liters per batch. Facilities are purpose-built or heavily customized. Think commercial plants with validated cleanrooms, automated control systems, and locked-down operating procedures.

Full-scale hallmarks:

- High-volume batches (hundreds to thousands of liters)

- High integration and automation

- Dedicated infrastructure and quality assurance systems

- Comprehensive regulatory compliance (e.g., GMP)

- Minimal tolerance for deviation or variability

At this point, your equipment may include large-scale fermenters or reactors, SCADA-integrated process controls, and validated instrumentation. Your team is no longer tweaking a process—they’re executing a validated, locked-down protocol with full documentation and traceability.

The shift to full-scale production is also a cultural change. Flexibility gives way to repeatability. Every process deviation is an event. Downtime is expensive, and yield loss impacts commercial viability.

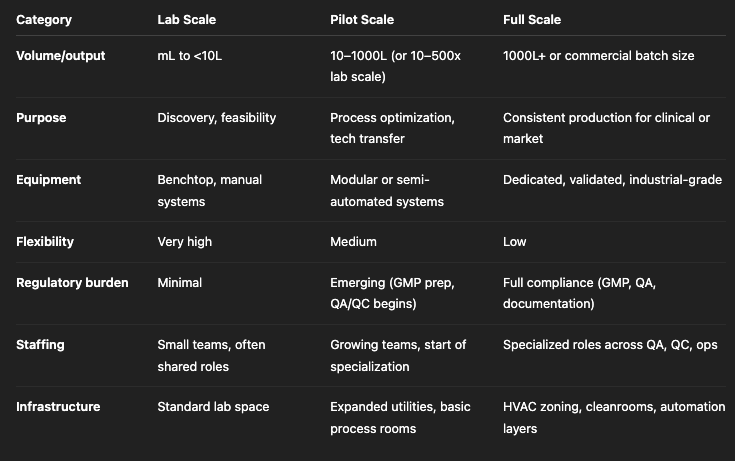

Comparing Lab, Pilot, and Full Scale

Understanding how these three phases differ helps you avoid missteps—like overbuilding for full scale when you haven’t nailed your pilot protocol, or underestimating infrastructure for even a modest pilot-scale ramp-up.

Here’s how the stages stack up:

Why Understanding Scale Matters

Not all mistakes come from bad science—many come from poor planning across different scales. We’ve seen teams invest in full-scale equipment before running pilot studies, only to discover major gaps in viability. We’ve also seen groups stretch lab-scale tools beyond their limits, ending up with backlogs, quality issues, or failed validations.

Knowing where you are on the scale-up journey helps you:

- Choose appropriate equipment and providers

- Define process parameters and scale process inputs

- Design cost-effective infrastructure that supports future growth

- Align staffing and training with operational complexity

- Build mathematical models that actually reflect real-world conditions

It also unlocks smarter financing. Leasing, modular buildouts, and phased implementation allow startups to scale processes without locking in capital on systems that may not fit long-term.

Takeaway: Planning for the right scale helps you avoid wasted CapEx, downtime, and operational churn.

Closing Thoughts: Scale with Intention

Lab scale is for discovery. Pilot scale is for proving the process. Full scale is for delivering consistent, validated output.

Each scale has unique challenges—whether it’s balancing mass transfer at small volumes, controlling variability at pilot scale, or meeting regulatory requirements at commercial scale. But success at any level starts with recognizing what that level demands.

Whether you're scoping a pilot plant, evaluating new technologies, or preparing for large-scale production, building with scalability in mind will pay off. That means designing around current needs while leaving space—physically, financially, and operationally—for change.

Scale isn’t just about size—it’s about making the right decisions at the right time, with the right infrastructure.